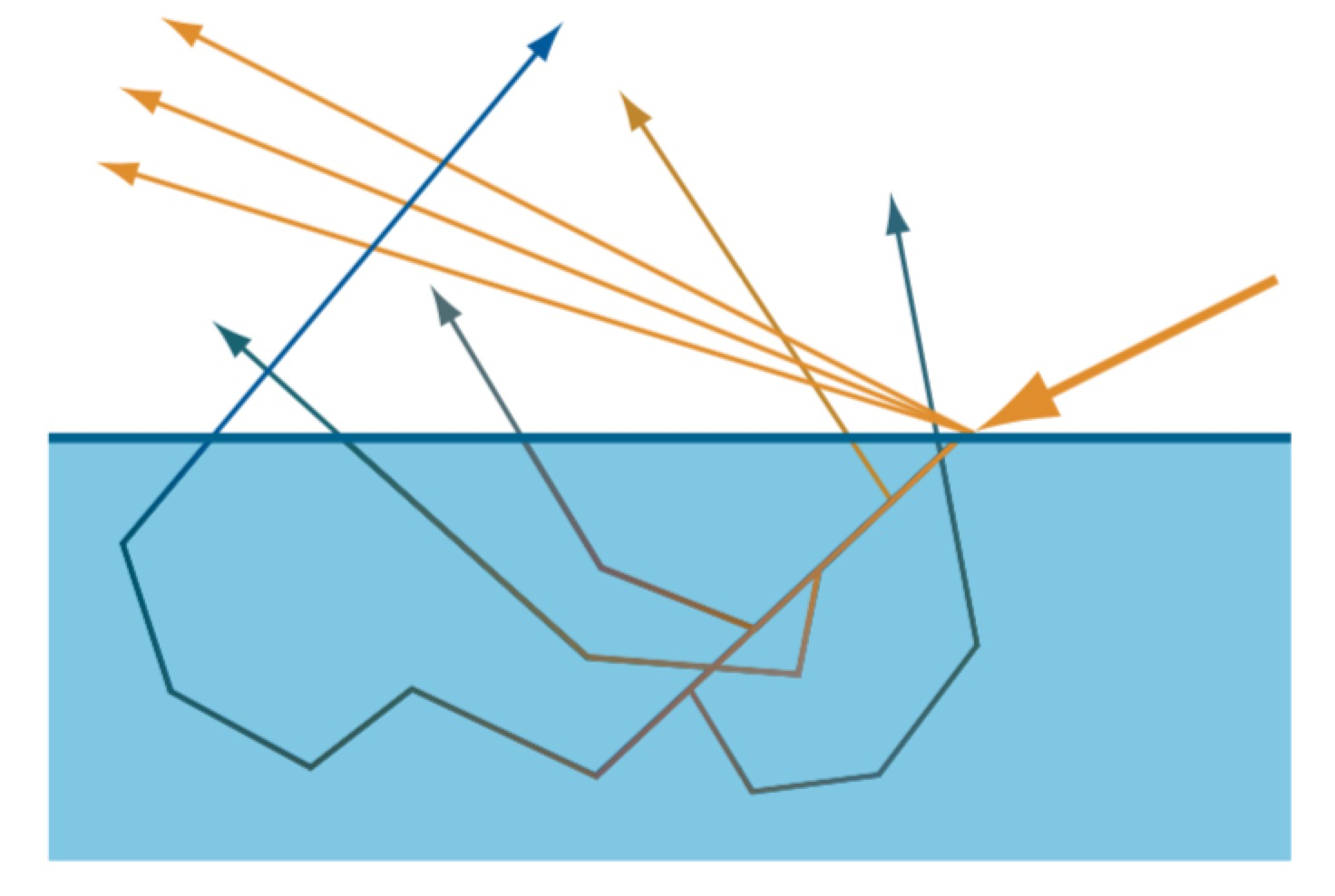

In some cases, the scale of scattering is relatively small, as for media with a high optical depth, such as human skin. Scattered light is re-emitted from the surface close to its original point of entry. This shift in location means that subsurface scattering cannot be modeled with a BRDF. That is, when the scattering occurs over a distance larger than a pixel, its more global nature is apparent. Special methods must be used to render such effects.

For most materials, the reflectance of light is usually separated into two components that are handled independently. 1 surface reflectance, typically approximated with a simple specular calculation; and 2 subsurface reflectance, which typically approximated with a simple diffuse calculation. However, these two components require more advanced models to generate realistic imagery of skin.

Skin Surface Reflectance

A small fraction of the light incident on a skin surface reflected directly, without being colored. This is due to a Fresnel interaction with the topmost layer of the skin, which is rough and oily, and we can model it using a specular reflection function.

Skin Subsurface Reflectance

Wrap lighting

A color shift is used to approximate the subsurface scattering. When used in this way, wrap lighting attempts to model the effect of multiple scattering on the shading of curved surface.

Normal Blurring

Stam points out that multiple scattering can be modeled as a diffusion process. The diffusion process has a spatial blurring effect on the outgoing radiance. Ma et al. determined the reflected light of scattering object and found that, while the specular reflectance is based on the geometric surface normals, subsurface scattering makes diffuse reflectance as if it uses blurred surface normal. Furthermore, the amount of blurring can vary over the visible spectrum. They propose a real-time shading technique using independently acquired normal maps for the specular reflectance and for the R, G, B channels of the diffuse reflectance.

Texture-Space Diffusion

Pre-Integrated Skin Shading

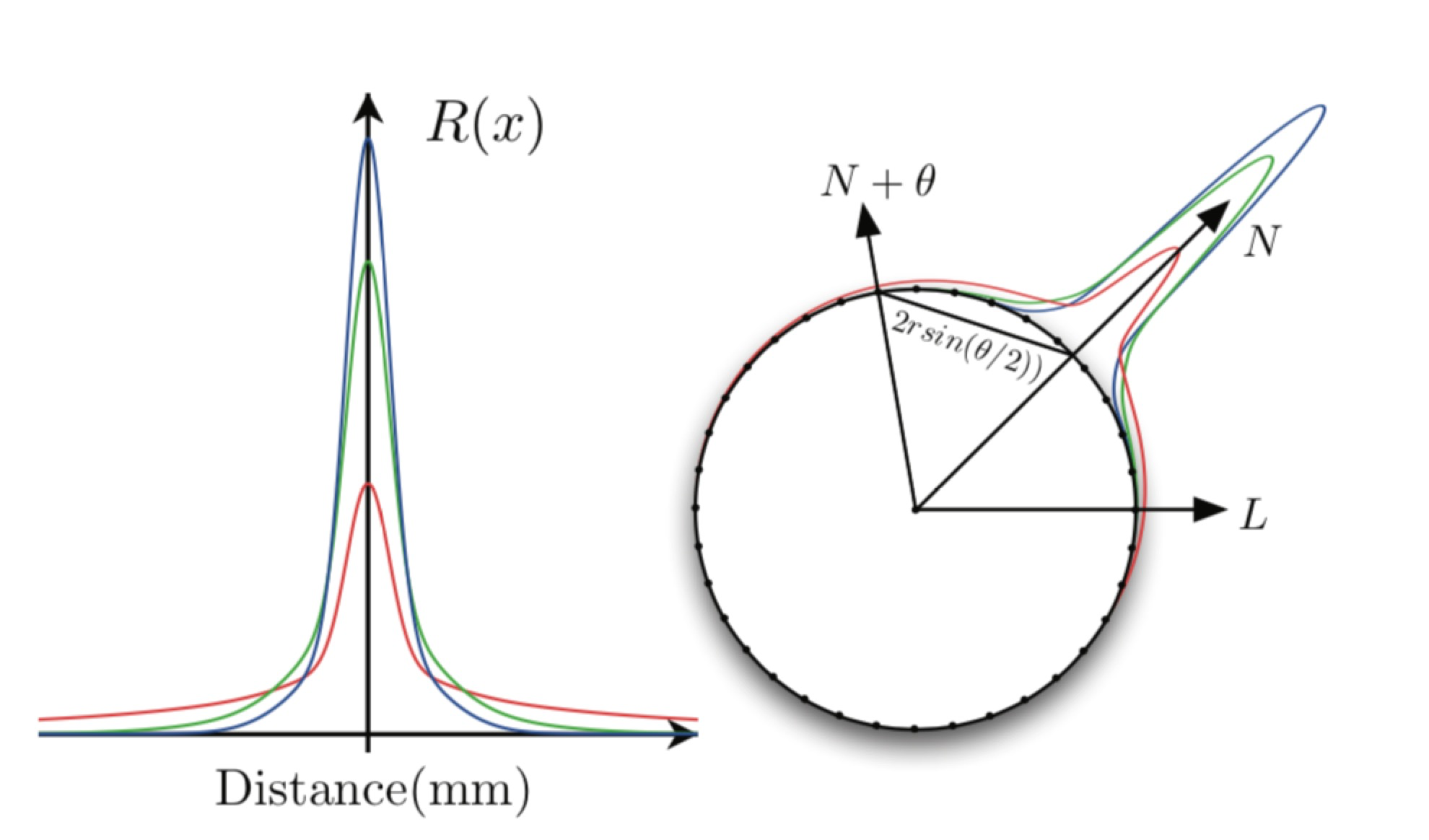

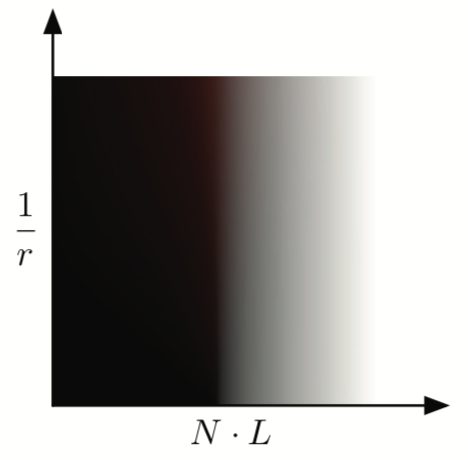

Pre-Integrated take a different approach to the problem of subsurface scattering in skin and have departed from texture-space diffusion. One approach to precompute the effect of scattered light at any point on a surface, was to simulate lighting from all directions and compress that data using spherical harmonics. $N\cdot L$ falloff is a primary cause of changing incident light, so it would be used as the first parameter to the measured diffuse falloff. To measure the effect of surface curvature on scattering, curvature is used as the second parameter. For each skin curvature and for all angles $\theta$ between $N$ and $L$, we perform the integration:

The difference was negligible and the ring integration fits nicely into a shader that is used to compute the lookup texture. The variable $R()$ refers to the diffusion profile, used the sum of Gaussians from the previous section. Rather than performing an expensive $arccos()$ operation in the shader to calculate the angle, the skin shading algorithm push this into the lookup, so the lookup is indexed by $N\cdot L$ directly.

This approximation will work very well on smooth surfaces without fast changes in curvature, but breaks down when curvature changes too quickly. To handle the effect of subsurface scattering on small surface details, Penner modifies the technique by Ma et al.. Since using four normals would require four transformations into tangent space and four times the memory, an approximation was investigated using only one mipmapped normal map. When using this optimization, they sample the specular normal as usual, but also sample a red normal clamped below a tunable mip-level in another sampler. Transform those two normals into tangent space and blend between them to get green and blue normals. Additionally, to get the scattering profile to span through shadow boundaries, the shadow penumbra profile can be used to bias the LUT coordinates. The trick used for shadows is to think of the results of shadow mapping algorithm as a falloff function rather than directly as a penumbra. When the falloff is completely black or white, things are completely occluded or unoccluded, respectively. However, what happens between those two values can be reinterpret. Define the representative shadow penumbra $P()$ as a one-dimensional falloff from filtering a straight shadow edge (a step function) against the shadow mapping blur kernel. For a given shadow value we can find the position within the representative penumbra using the inverse $P^{-1}()$ (assuming monotonically decreasing). In the end, two-dimensional shadow-lookup integration is a simple convolution:

Screen-Space Diffusion

Reference

- Chapter 14.6 “Subsurface Scattering”, in Real-Time Rendering Four Edition

- d’Eon, Eugene, and David Luebke, “Advanced Techniques for Realistic Real-Time Skin Ren- dering,” in GPU Gems 3

- “Pre-Integrated Skin Shading” in GPU pro 2